Questions:

- What are the children doing?

- Why are they doing it? Where do you think the order for them to do it comes from?

- How do you think that action could have affected their lives overall, or the lives of their parents and families?

We can use this clip from the 1990 film Lenin, the Lord and Mother to discuss two important elements of the communist regimes in the Eastern bloc. First of all, the scene is placed at a key moment in history – the early 1950s, when the show trials were taking place in Czechoslovakia and in the other countries that had fallen under the Soviet Union’s influence after WWII. In the early years of the communist regimes, under the leadership of Soviet leader Joseph Stalin, the show trials were a strategy that the regimes used to demonstrate what the penalties for disloyalty to the Communist Parties would be. Thousands of Party members and “class enemies” (including members of other political parties, freedom fighters, or wealthy farmer, for example) were marked as disloyal, whether or not they actually were, and chosen to be very publically purged. These purges reached even to the highest echelons of the Parties. Those deemed to be the worst traitors were then sentenced in the show trials, trials where the verdict was decided before they even began and which were broadcast widely for the whole country to see, all as a strategy to scare the populace into falling in line.

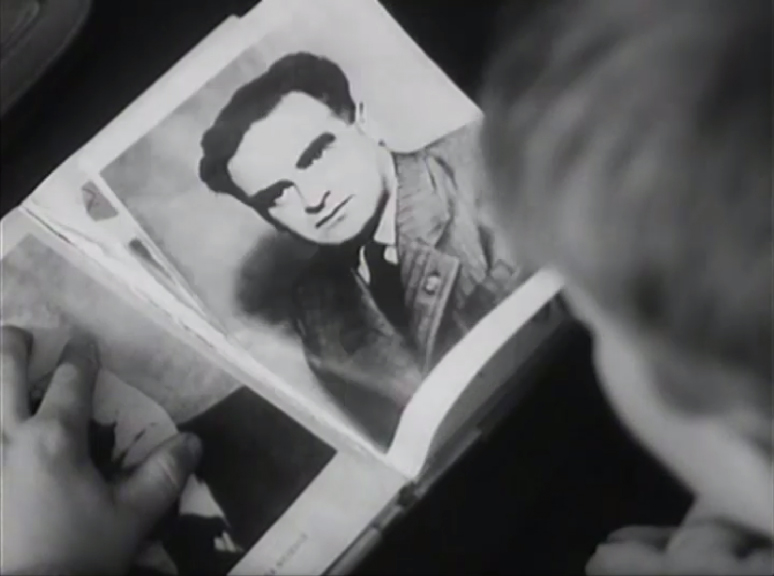

The action in the clip, of the children tearing out pictures of one of these so-called traitors, illustrates the degree to which the regimes required that their citizens outwardly agree with them. The students, of course, would have had no particular opinion about the man in question and whether he betrayed the country, and then the teacher passes on the party line, dictating what to believe. The teacher herself, then, brings up another interesting question – does she believe that the man in the picture betrayed the country? There were undoubtedly many staunch communists and Party supporters throughout the communist period, but it was not always easy to tell the difference between those who were merely loyal to it for one reason or another and those who had absolute faith in the fairness of its policies and could square that with their own experiences and consciences. Tearing out the pages also, however, illustrates the level of control that the regimes attempted to hold over all areas of life, to the point of even attempting to adjust the history that children would learn in schools.

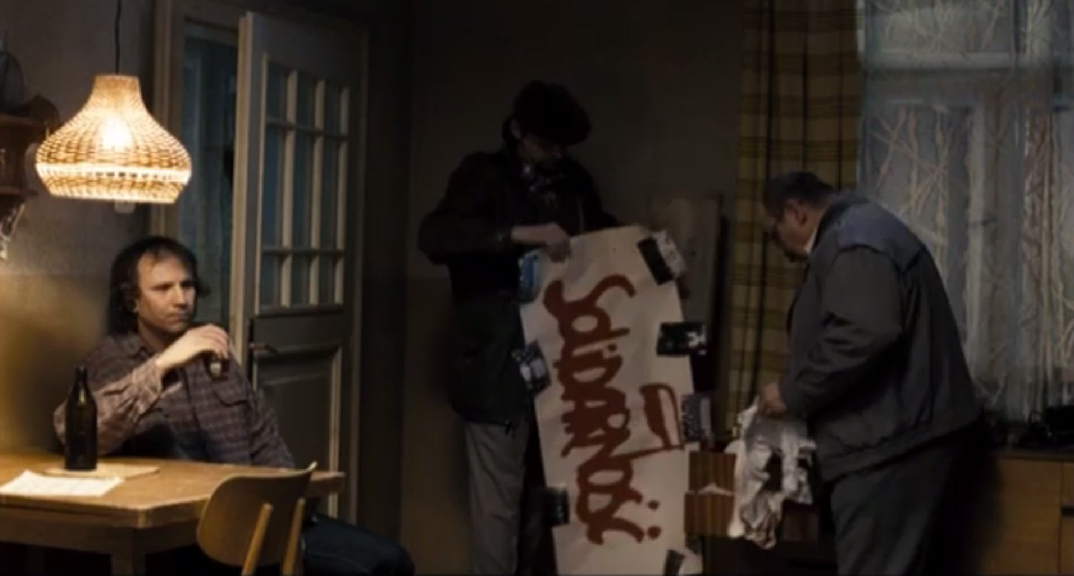

Of course, there were always individual people who chafed at that level of control. The following section shows an example of the regime’s reaction to one of them, but it takes place about 30 years later, in the 1980s. During the 1950s, the punishments for such transgressions would have been much harsher.

Explore